Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

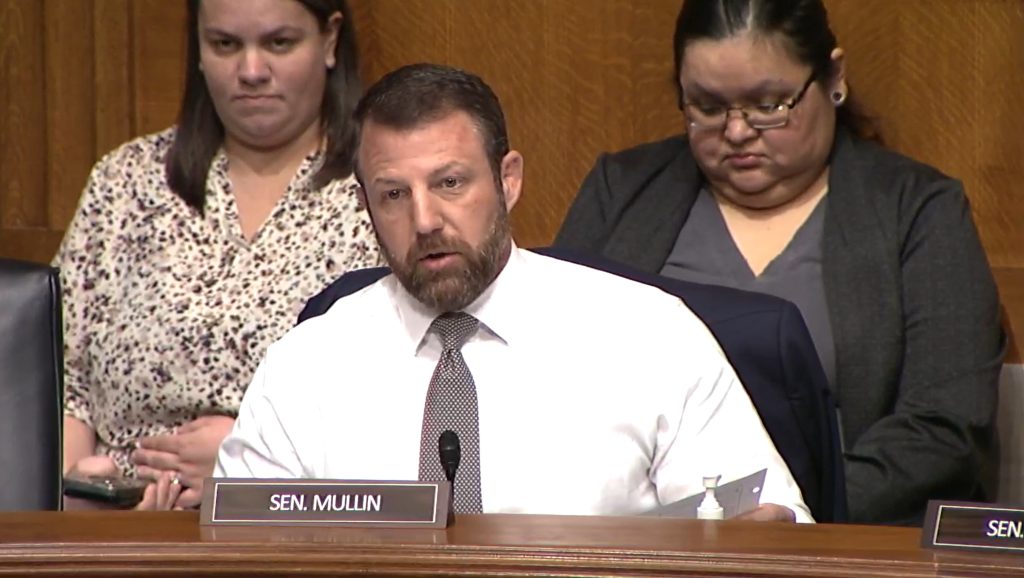

U.S. Sen. Markwayne Mullin (R-OK) is enrolled in the Cherokee Nation, making him only the second Cherokee Nation citizen ever to serve in the U.S. Senate.

Correspondent Matt Laslo has the story from Washington.

Sen. Mullin spent five terms in the House before moving to the Senate this year.

The House tends to be rowdier, which may be why last month, Sen. Mullin came out swinging – almost literally – when he challenged International Brotherhood of Teamsters president Sean O’Brien to a fight before the Labor Committee Chair, U.S. Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) put an end to it.

Sen. Mullin: “Want to do it now?”

President O’Brien: “I’d love to do it right now.”

Sen. Mullin: “Well, stand your butt up then.”

President O’Brien: “You stand your butt up.”

Sen. Sanders: “Hold it. Stop it. Alright. Sit down. You are a United States senator! God knows the American people have enough contempt for Congress.”

Sen. Mullin is a former professional Mixed Martial Arts (MMA) fighter and brings that fighting spirit with him – not just when questioning union bosses.

While the Senate is boring compared to the House, Sen. Mullin says the Senate has grown on him.

“Much different. Actually, I like it better. Now that I’m here, I like it better. I didn’t at first, but I like it better here now.”

In the House, Sen. Mullin was one of 435 members.

To pass a measure you’re passionate about, you need to convince 217 of your colleagues to agree.

Being one of only 100 senators has its perks.

“You can be more effective, I think, by yourself on the issues that are important to you. Like, you were just talking about Native news, you can be more impactful on Native issues as a senator than you can in the House, just because you can do a lot more by yourself, rather than have to have 218 before you can do anything.”

Sen. Mullin says another perk of being a senator is that federal agencies are much more responsive to him than they were when he was just one in the crowded and rowdy House of Representatives.

He says that’s been especially helpful working on tribal issues with officials at the Interior Department and Bureau of Indian Affairs.

“Getting BIA to engage with you is much easier. Getting Interior to engage with you, much easier interest and those are all areas that are vitally important.”

As for getting union bosses to engage with him?

“Depends on which one they are (laughs).”

Daylene Redhorse fastens a plus code address plate to a home in southeast Utah’s Navajo Nation. (Courtesy Rural Utah Project)

Thousands of homes on the Navajo Nation have gained official addresses.

The four-year project in southeast Utah recently wrapped up.

KUER’s David Condos reports.

Without a home address, a lot of things become complicated or even impossible.

Registering to vote.

Getting online orders delivered.

Making sure an ambulance can find you.

That was the reality for much of Utah’s Navajo Nation before the advocacy group Rural Utah Project began going door to door in 2019.

This month, the project finished assigning addresses to 3,113 homes.

Daylene Redhorse led the endeavor.

“I am happy. I am just overjoyed that I’ve completed this. And … I think everybody deserves a physical address.”

The project gave each home a plus code, a number that pinpoints a location based on longitude and latitude rather than a street name and house number.

Tiffany Bah Charley is a public information officer with the Navajo Nation Human Rights Commission.

She says the example in Utah could boost efforts to address buildings in Arizona and New Mexico.

“For Navajo Nation, it’ll be a good positive impact for them to utilize plus codes … It’s just a matter of getting out there and doing the work.”

Redhorse with the Rural Utah Project says her next mission is to get more Navajo registered to vote and increase their representation.

Get National Native News delivered to your inbox daily. Sign up for our newsletter today.