Koahnic Broadcast Corporation (KBC) and Native Voice One (NV1) brought the energy and personality of the Native Youth Olympic (NYO) Games to the radio.

The KBC news team led by Antonia Gonzales broadcast three special one-hour live programs, Alaska’s Native Voice: Live from NYO 2024 on Thursday, April 25, Friday, April 26, and Saturday, April 27.

Subscribe to the NV1 podcast to get all three episodes on demand or listen below.

The program featured interviews with athletes, coaches, NYO leaders, and veterans. The traditional games, which were originally depended on for survival, continue to develop the strength and skill of generations of Alaskan Native people. The NYO carries on the games by encouraging young people to strive for their personal best.

Producer/host Antonia Gonzales from National Native News was joined by Jill Fratis, Hannah Bissett, and Rhonda McBride from our flagship station KNBA with commentary and floor coverage.

Day One

Day Two

Day Three

NYO 2024 PHOTO GALLERY

NYO 2024 VIDEO GALLERY

Voices of NYO

Stories of NYO

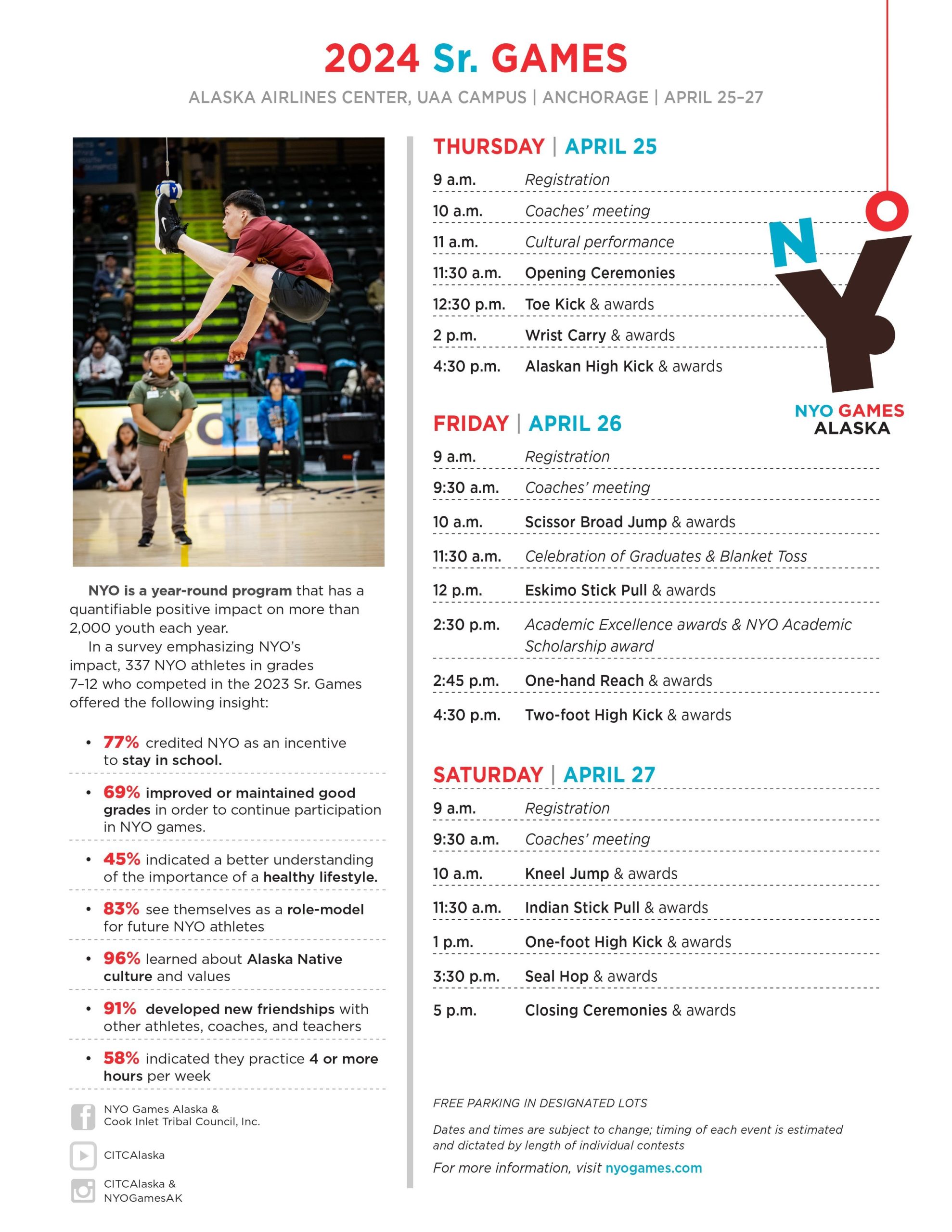

After three days of competition at the statewide Native Youth Olympic (NYO) Games in Anchorage, students have returned home to show off their medals for traditional games like the Two-Foot High Kick, the Kneel Jump, and the Seal Hop.

Rhonda McBride from our flagship station KNBA has more.

This year more than 400 students took part in the games that are not so much about competition, but an opportunity for each athlete to do their best.

In Native Youth Olympic Games, competitors often try to encourage each other. Students say it’s the spirit of the games which sets them apart.

“My name is Camille. I’m from Kodiak. I love the togetherness that NYO brings us together. My name is Grayson Damien. I’m from Alakanuk. And I love Indian Stick Pull. My name is Maya Bogar and I’m from Chickaloon Native Village and my favorite thing about NYO is probably sportsmanship. My name is Merlin Machien. My favorite thing about NYO is how people connect.”

The games drew about 2,000 spectators a day, including elders like Peter Black, originally from Hooper Bay. He says although Anchorage is a big village, the games bring back old memories.

“I love NYO, because I used to do the same thing when I was growing up, but only in a village.”

57 teams competed in this year’s games, hosted by the Cook Inlet Tribal Council.

The 2024 Native Youth Olympics wrapped up after three days of competition.

KNBA’s Jill Fratis reports.

This year’s games saw more than 440 athletes, and 57 teams from all over the state. Koahnic Broadcast Corporation along with Native Voice One had an hour-long show every day of the event with former athletes, coaches, record holders, and organizers discussing the history, purpose, and changes that have happened over the years with the event.

Here’s some of the descriptions from the Cook Inlet Tribal Council’s YouTube page of the events that played on the jumbotron before every competition:

“The kneel jump was played to develop the skills hunters needed for jumping up quickly, off of ice, or off the ground, in the event they needed to get away from another animal that snuck up behind them. The seal hop was played to help build strength and endurance to pain while they hop along the ice imitating the motion of a seal. And when they got close enough to the seals taking naps on the ice, they would grab their harpoon off their back, and harpoon the seals.”

The games were held at the Alaska Airlines Center in Anchorage. People of all ages from newborns, infants to elders gathered at the arena. Native Youth Olympics began in 1971 by students who were living in Anchorage Boarding schools, and wanting to introduce the Native traditions of how their ancestors used these techniques to hunt, fish, and survive.

“My name is Maya Boger, and I’m from Chickaloon Native Village: my favorite thing about NYO is probably the sportsmanship. My name is Merlin Machen: my favorite thing about NYO is how people connect! When they travel. My name is Gracen Damian: I’m from Alakanuk. I love Indian Stick Pull. I’m Peter Black, originally from Hooper Bay: and I love NYO because I used to o the same thing when I was a kid growing up, only in the village.”

Brian Walker is Island Inupiat and Athabascan. Currently, he’s a Student Specialist for Indigenous Education at the Anchorage School District. Walker says that while these events help keep the history of the Indigenous past of hunting and fishing alive, it also helps educate those who don’t know about the culture.

“But when we share the knowledge of these games, to not only our people, but for non-Indigenous people. It really helps non-Indigenous (people) understand who we are, where we came from, and our traditional values, of looking back of where our people came from, and where they’re going. It’s so important.”

There is also Junior NYO, student athletes have a chance to be a part of those games from 1st-12th grade, and after grade school, they can even partake in the Arctic Winter Games, and the Winter Eskimo Indian Olympics.

Nicole Johnson is Inupiaq and has taken part in traditional games since she was in 5th grade. She’s won more than a hundred medals over the years and was inducted into the Alaska Sports Hall of Fame in 2017. This year, she was the head race official for NYO. She says once you become involved in Native Youth Olympics in any form, you always come back.

“It doesn’t just end at your senior year. Some people think it might. But it doesn’t, you can always come back and volunteer. You can offer your coaching. You can coach for teams. You can come back as an official. You can volunteer, there’s so many different opportunities with NYO to volunteer.”

The Native games are also gaining recognition outside of Alaska.

After three days of competition at the Statewide Native Youth Games in Anchorage, students have returned home to show off their medals for

traditional games like the Two-Foot High Kick and the Kneel Jump.

But, in their mind’s ear, they might hear this sound (seal call). Imagine hearing lots of these seal calls in a stadium full of people.

KNBA’s Rhonda McBride sought out the source of these sounds, a tradition that is as old as the games themselves.

The sound of enthusiastic crowds often fills the air at the Alaska Airlines Center, but at the Native Youth Games you hear that and more.

Although Samuel Mecham perfected the seal call during seal hunts in his hometown of Unalakleet, he’s happy to belt it out across a sea of people.

“Oh, it’s fun. It gets everybody riled up. And it gets people’s attention. And also, it’s like our way of shouting and cheering on your teammate. So like at a track meet, you’d yell at your teammates. Right? You’d yell their name and say keep on going. But here you would do a seal call.”

As the master of ceremonies at the Native Youth Games, Marjorie Tahbone uses the seal call to get athletes pumped up.

Tahbone says seals are naturally curious creatures. Traditionally, hunters used the call to distract them.

“The hunters would have to mimic a seal and get as close as they could, close enough where they could harpoon it.”

The seal call was also used to signal hunter success – a joyful sound that Tahbone says helps to bring the sounds of land and sea into the city.

“Organize your throat, your mouth in a certain way. (Trilling sound) You hear that. It’s that (Raven Sound). Also from his seat in the stadium, you can hear his call of the loon,” said Joey Cross.

Joey Cross/Chenega Raven Caller: I learned this from a friend (Loon Sound). By doing that I learned I could make it smaller. Also a little whistle (whistle sound).

The sounds from villages near and far add excitement to games like the seal hop, where athletes race across the stadium in a push up position hopping as far as they can hop. Caelynn Carter is from the Mat-Su School District, excited she has finally mastered the seal call.

“ I just figured it out today and I haven’t stopped. It’s a great way to cheer someone on. It’s a lot cooler than clapping. (Seal call) ”

The games played here were traditionally used to build endurance for hunting and fishing in the extreme cold, but Marjorie Tahbone says they have their use in today’s world, especially the seal call.

“When you’re walking down the aisle of Walmart and you hear a Oot, other people will start doing it three aisles down. If you can’t find me, seal call and we’ll find each other.”

So if you hear that sound in the store…. you’ll know what it means.

ABOUT THE TEAM

Antonia Gonzales is host and producer of the three one-hour special live programs, “Alaska’s Native Voice: Live from NYO 2024” on Thursday, April 25, Friday, April 26, and Saturday, April 27, 2024 at 12 p.m. AKDT.

- KNBA Producers/Reporters Jill Fratis, left, Rhonda McBride, and Hannah Bissett.

The program features interviews with athletes, coaches, fans, and other attendees.

The traditional games, which were originally depended on for survival, continue to develop the strength and skill of generations of Alaska Native people. The NYO carries on the games by encouraging young people to strive for their personal best.

View this post on Instagram