Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

As the Guatemalan government prepares to use force against the unprecedented uprising led by Indigenous groups, thousands of citizens in that Central American country are still joining actions against what they see as attempts to block a reformist president-elect from taking power. Maria Martin reports on the second week of the uprising against corruption and authoritarianism in Guatemala.

Bus loads of new protesters entered Guatemala city this week from the largely Indigenous provinces of San Marcos and Huehuetenango. The protests and the more than 100 blockades across the country are only getting bigger in the wake of recent statements by President Alejandro Giammattei in a nationally televised speech, the outgoing president said protesting Guatemalans that have virtually shut down the country were “poquitos”.

“They’re only a few”, President Giammattei said of the hundreds of thousands out in the streets and highways.

At the major cross roads called Cuatro Caminos, Indigenous TikTok influencers The Pacheco Brothers sent a message in response to Guatemala’s president.

Rafael Pacheco: “ We are many and we’ll continue fight the corrupt government .”

As the protests grow, tensions are rising, and violence has broken out in some places.

Outgoing President Giammattei blames President-elect Bernardo Arévalo for “encouraging the protesters.” Arévalo says the government is using infiltrators to incite violence, so it can declare a state of siege.

@_rafaelpacheco Dijo el presidente que somos un grupito de personas aca lo desmentimos 🇬🇹🇬🇹🇬🇹🇬🇹@Antonio Pacheco ♬ Así Fue – En Vivo Desde Bellas Artes, México/ 2013 – Juan Gabriel

Nationwide, millions of barriers – like dams – make it hard for fish to move freely and lay eggs.

Nationwide, millions of barriers – like dams – make it hard for fish to move freely and lay eggs.

Now, the federal government is spending more than $200 million to reopen spawning grounds for fish.

That includes an effort to recover an endangered species that’s sacred to the Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe in Nevada.

The Mountain West News Bureau’s Kaleb Roedel has more in a report edited by Jennifer Coombes.

At the Pyramid Lake Paiute Reservation in northern Nevada, rolling mountains cloaked in pale-green sagebrush unfold for miles like a painting that never ends.

Standing at an overlook in these hills is the tribe’s chairman, James Phoenix. He’s watching the Truckee River rush over Numana Dam, an irrigation diversion.

As a kid, Chairman Phoenix fished in these waters for Cui-ui – sucker fish that aren’t found anywhere else in the world.

“Bringing them to shore and then cutting and filleting them, that’s what my dad had taught me. And I got to experience that’s how he was taught when he was young.”

The tribe refers to themselves as Cui-ui Tucutta in their Native language, which means “the Cui-ui eaters.”

But tribal members stopped catching them back in the 1980s as the fish population plummeted.

A big reason for the decreased fish population is this dam.

It was built more than 100 years ago to divert river water to the reservation for farming and ranching. But it’s been a barrier for migration of the endangered cui-ui and threatened Lahontan Cutthroat Trout – another fish crucial to the tribe.

Chairman Phoenix says the previous tribal council discussed removing or modifying the dam, but kept running into the same hurdle.

“A lot of funds weren’t available.”

That finally changed. The tribe is getting more than $8 million from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law to modify the dam.

The money will be used to build a large underwater ramp – stretching from bank to bank – so fish can swim up and over the dam.

The project, which recently broke ground, will reopen 65 miles of river for their migration.

Chairman Phoenix says that will impact more than the tribe’s culture.

“It’s important to our economics. We rely on tourism and fishing. We get a lot of anglers that are coming in seasonally, so it’s really big for us.”

Get National Native News delivered to your inbox daily. Sign up for our newsletter today.

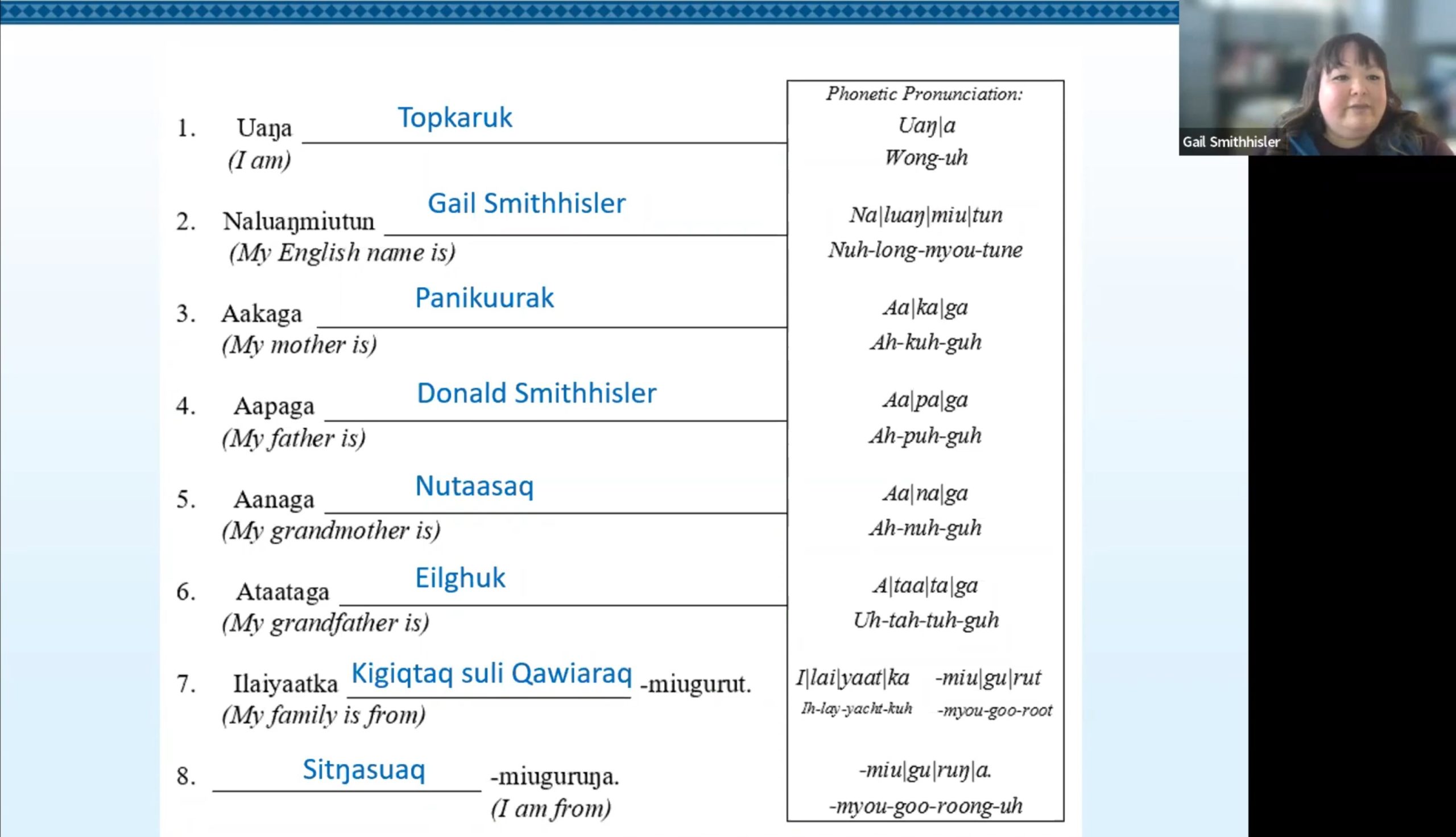

Alaska is home to more than 20 Alaska Native languages, but over the last century, the number of fluent speakers has declined.

Alaska is home to more than 20 Alaska Native languages, but over the last century, the number of fluent speakers has declined.

The Cherokee Nation in Oklahoma has collaborated with AT&T on an internet and digital learning center.

The Cherokee Nation in Oklahoma has collaborated with AT&T on an internet and digital learning center.

Three Democratic U.S. lawmakers have introduced legislation to officially recognize the second Monday of October as Indigenous Peoples’ Day on the federal level.

Three Democratic U.S. lawmakers have introduced legislation to officially recognize the second Monday of October as Indigenous Peoples’ Day on the federal level.

The memorial at Wounded Knee, one of the most prominent landmarks on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, was recently vandalized.

The memorial at Wounded Knee, one of the most prominent landmarks on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, was recently vandalized. Assistant U.S. Attorney

Assistant U.S. Attorney