Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

The stories of Indigenous Americans are as valuable as any other, but those stories aren’t always told accurately or helpfully. Inclusion of Native voices in media are crucial, but how can we create those opportunities?

South Dakota Public Broadcasting’s C.J. Keene has more.

Journalism, with its degree requirements and institutional power, can be an intimidating field for many to enter.

The inclusion of new voices in the news field could help break that wall down though.

Native journalists like Amelia Schafer are working across America for organizations like Indian Country Today, Koahnic Broadcast Corporation, or for your local indigenous publication, but Schafer says there is work yet to do.

“Native people have the sensitivity to tell Native stories in a way that is not as harmful as someone as someone who is uneducated in the community – or is educated on stereotypes of the community. It’s more empowering to be able to tell these stories that effect your community. Native reporters – it’s hard, but it’s also so rewarding because we’re able to tell these different stories in a way the community wants to be heard.”

Schafer says if you’re a young person with an interest in news – don’t stop.

“If I would have had somebody to tell me back then that it’s okay to keep perusing this even though there are people who don’t understand you or don’t want to understand you – that was something I faced in high school – it’s something that’s worth perusing. Native-led organizations like ICT can really help to empower reporters and give you that support that you need, and the ground of mutual understanding.”

It starts with school newspapers and student-broadcasting opportunities.

For Diana Cournoyer, executive director of the National Indian Education Association, there is equal value to be found in the perspectives unique to indigenous journalists.

“We have a lot of storytellers who probably would want to be journalists, but the two schools of thought don’t mesh. We are storytellers first and foremost – to be a storyteller, you also have to be a story-listener.”

Further, Cournoyer says opportunities to enter the field, like journalism internships or fellowships, simply don’t exist to the same degree on reservations than off.

Courtesy Rep. Mary Peltola / Facebook

U.S. Rep. Mary Peltola (Yup’ik/D-AK) says she’s ready to return to work at the nation’s capital.

Rep. Peltola has been spending time with family, following the loss of her husband, Gene “Buzzy” Peltola, who died in a plane crash on September 12.

In a statement, Rep. Peltola said the past few weeks have been some of the most difficult in her life, and that she appreciated how Alaskans have given her the space to celebrate her husband’s life with her family.

“The kindness and generosity that you have shown represents Alaska at its best.”

In the statement, Rep. Peltola talked about the federal shutdown, which she said was “barely avoided and could have hit Alaska’s military families, seniors and children hard.”

Rep. Peltola said after watching all the partisan politics in Washington continue, as another shutdown looms, she’s anxious to return to Congress.

She says she will continue to mourn her husband, but also knows he would want her to get back to work.

Courtesy Lac Courte Oreilles Tribal Governing Board

In Wisconsin, the Lac Courte Oreilles Tribal Governing Board has responded to a letter from the LCO Ojibwe School Superintendent Jessica “Hutch” Hutchinson about a rise in behavior and dress among middle school students that has been associated in the past with gang affiliation.

Tribal officials are asking parents and community members to teach young people about the dangers of gang activity, and to remind everyone of the tragedies that happened to Lac Courte Oreilles in the late 90’s and early 2000’s.

That’s when gang violence claimed the lives of two young tribal members and eventually, the imprisonment of dozens of community members.

According to officials, the LCO Ojibwe School will begin dealing with associated behavior as a “Class I” offense, which may result in in-school suspensions or out-of-school suspensions.

The Tribal Governing Board says they fully support necessary actions to protect the community as a whole.

Get National Native News delivered to your inbox daily. Sign up for our newsletter today.

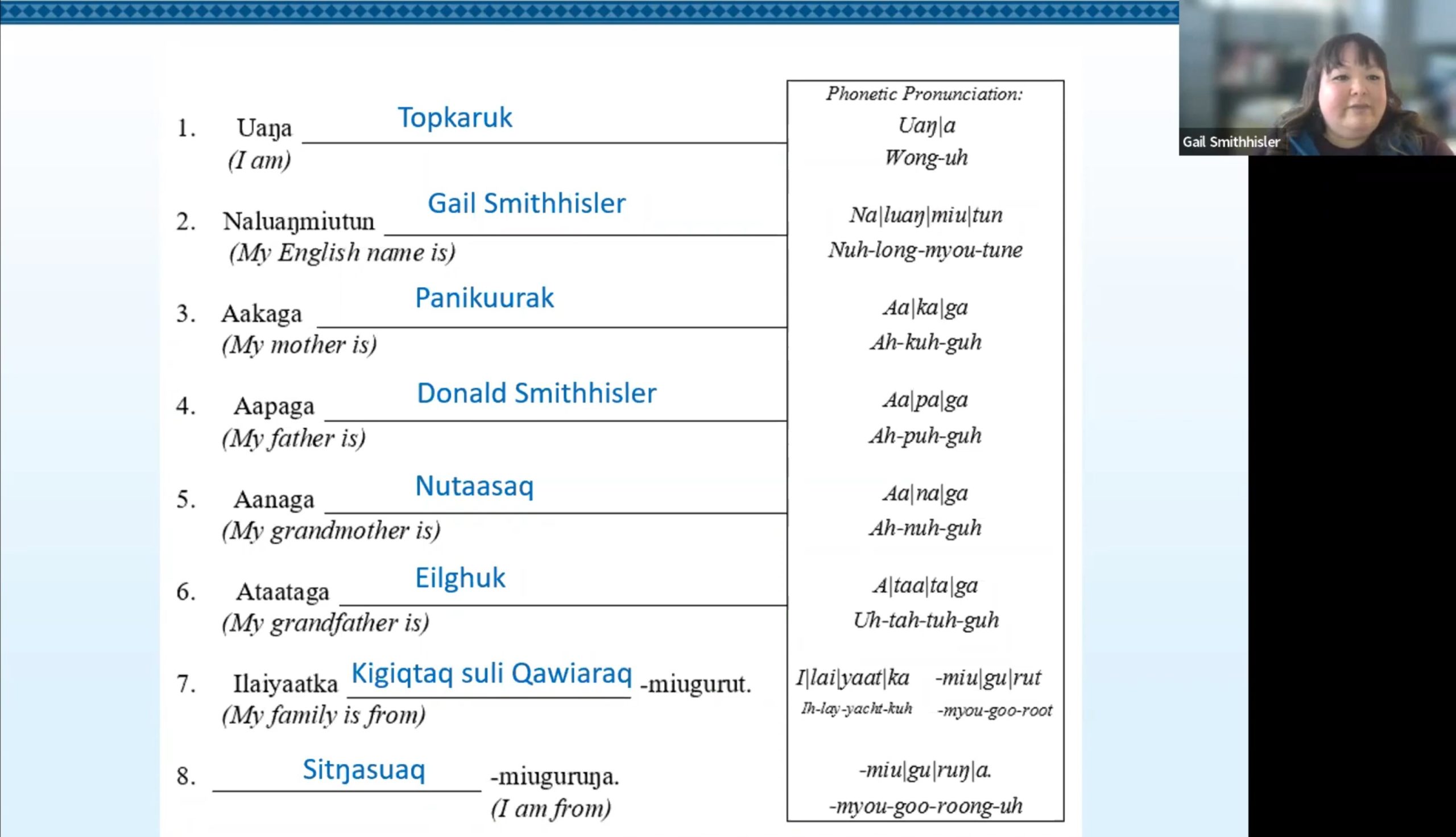

Alaska is home to more than 20 Alaska Native languages, but over the last century, the number of fluent speakers has declined.

Alaska is home to more than 20 Alaska Native languages, but over the last century, the number of fluent speakers has declined.

The Cherokee Nation in Oklahoma has collaborated with AT&T on an internet and digital learning center.

The Cherokee Nation in Oklahoma has collaborated with AT&T on an internet and digital learning center.

Three Democratic U.S. lawmakers have introduced legislation to officially recognize the second Monday of October as Indigenous Peoples’ Day on the federal level.

Three Democratic U.S. lawmakers have introduced legislation to officially recognize the second Monday of October as Indigenous Peoples’ Day on the federal level.

The memorial at Wounded Knee, one of the most prominent landmarks on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, was recently vandalized.

The memorial at Wounded Knee, one of the most prominent landmarks on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, was recently vandalized. Assistant U.S. Attorney

Assistant U.S. Attorney  The Alaska Federation of Natives has sided with the federal government in a legal battle over salmon management on the Kuskokwim River, as

The Alaska Federation of Natives has sided with the federal government in a legal battle over salmon management on the Kuskokwim River, as